I read an article recently that described the work of one of my old college professors, Paul Harris, a developmental psychologist who now works at Harvard’s education school. The work in question is about questions. Contrary to much received wisdom about how young children learn about the world they live in, which asserts that they do so by testing out their environment via a behavioral succession of trial and error, Harris contends that key to child development is an extraordinary volume of question-aksing. A 2007 study by psychologist Michele Chouinard found that children between the ages of two and five ask one to three questions per minute, equivalent to 40,000 questions over the span of those first crucial years of cognitive life.

This past academic year, I have been passing on the gift of teaching, first offered to me by Professor Harris 20 or so years ago, to my own college students as an adjunct professor at my local university. I fully admit that for students who have been brought up on a pedagogical diet of information delivery and recovery, my teaching style may well have been something of a pain. Full-time educators like to call it the Socratic method, which is just another way of saying that as the teacher, you ask a lot of questions.

I doubt that we got anywhere near 40,000, but I would hope that my students will have at the least got the impression about Theology this year that there are many, many more questions than there are easily articulated answers. If that is even partially true as a teaching outcome, then I will have succeeded. For it strikes me that our culture is so entrenched at present with easily articulated, or at times barely articulated answers, that the pedagogy of our public discourse almost wants to rule out questions before they are even enunciated.

I doubt that we got anywhere near 40,000, but I would hope that my students will have at the least got the impression about Theology this year that there are many, many more questions than there are easily articulated answers. If that is even partially true as a teaching outcome, then I will have succeeded. For it strikes me that our culture is so entrenched at present with easily articulated, or at times barely articulated answers, that the pedagogy of our public discourse almost wants to rule out questions before they are even enunciated.

The current daily dose of evening news Washington politics has that particular strain running right through the middle of it. Yet it is not just political life that suffers from an aversion to interlocution. For many of the students who ended up in my classroom this semester on a Thursday evening, the education system that had prepared them for college has increasingly preferred to view the cultivated mind as the one that can absorb what others think rather than one that can think for itself.

Yet, it is not enough for us to be people who will be inclined to ask questions; of ourselves or of others. Incisive intellectual discovery requires us to ask the right questions. Duncan Watts, who works for Microsoft Research, and is author of the book, ‘Everything Is Obvious: Once You Know the Answer’, argues that a ‘good’ question is both ‘interesting’ and ‘answerable.’ As a theologian, who does not work for Microsoft, I would contend with Watts’ here, and ask whether the most productive questions for theological inquiry are actually those that capture our interest because they evade being ‘answerable’, at least at first.

Yet, it is not enough for us to be people who will be inclined to ask questions; of ourselves or of others. Incisive intellectual discovery requires us to ask the right questions. Duncan Watts, who works for Microsoft Research, and is author of the book, ‘Everything Is Obvious: Once You Know the Answer’, argues that a ‘good’ question is both ‘interesting’ and ‘answerable.’ As a theologian, who does not work for Microsoft, I would contend with Watts’ here, and ask whether the most productive questions for theological inquiry are actually those that capture our interest because they evade being ‘answerable’, at least at first.

All of this has given me cause to reflect on the life of church community these past few weeks. In the life of our wider church, which as Episcopalians we call a ‘diocese’, I am leading a group that is charged with shepherding the process to find a new bishop to lead our church community. It seems to me that the success of that work will depend greatly on our ability to ask the right questions of ourselves and of God. The same can be said for our individual lives as they are played out in the company of others. The Church over time has called such a posture, discernment – the art of leaning into the Spirit of God, listening for the ways by which the divine life is moving within our own. Done well, it has the capacity to enrich our lives by raising up questions we hadn’t even realized we needed to ask.

During one of my students’ presentations a few weeks back, one of them made the case for Christ’s presence in the sacraments as akin to the work of a supervisor. He stated that given that Jesus had begun certain practices in the life of the Church, Jesus wished to remain present within them in order to make sure we are keeping good on the promise, that we are remaining faithful to the vision of life together he had first intended. I told the young man making his presentation that ‘Christ as Supervisor’ was an image of God that would ring true for many in today’s workplace culture, although I am not sure always in a good way. That said, it is an intriguing way in to think about the divine life among our own: that ‘Christ the questioner’ might be present among us, asking of us if we as the Church have remained true to our calling.

During one of my students’ presentations a few weeks back, one of them made the case for Christ’s presence in the sacraments as akin to the work of a supervisor. He stated that given that Jesus had begun certain practices in the life of the Church, Jesus wished to remain present within them in order to make sure we are keeping good on the promise, that we are remaining faithful to the vision of life together he had first intended. I told the young man making his presentation that ‘Christ as Supervisor’ was an image of God that would ring true for many in today’s workplace culture, although I am not sure always in a good way. That said, it is an intriguing way in to think about the divine life among our own: that ‘Christ the questioner’ might be present among us, asking of us if we as the Church have remained true to our calling.

Wherever you are on your journey, I pray that you can keep on asking the questions.

Picture this scene*. It’s the Day of the Dead. On the outside, across the city of Tijuana, Baja California, the sounds of the fiesta, of music and laughter can be heard. People are enjoying the finest of food and the best of company, and they are remembering all those who have come before them whom they love yet see no more. On the inside, of La Mesa state penitentiary, there are others who are not seen, yet loved, lost in a dark place, yet not altogether bereft of the light. Sixteen men are barricaded in on the third floor. The power has been cut-off, and the only light is cast by the flames rising from the cell windows. They are up there, in that state, because something in them had snapped. Deprived of water and food, brutalized day after day, these men had decided to take matters into their own hands, and take over part of the prison.

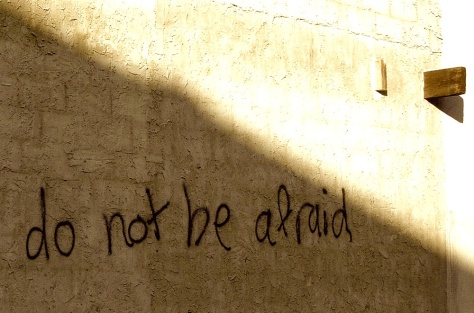

Picture this scene*. It’s the Day of the Dead. On the outside, across the city of Tijuana, Baja California, the sounds of the fiesta, of music and laughter can be heard. People are enjoying the finest of food and the best of company, and they are remembering all those who have come before them whom they love yet see no more. On the inside, of La Mesa state penitentiary, there are others who are not seen, yet loved, lost in a dark place, yet not altogether bereft of the light. Sixteen men are barricaded in on the third floor. The power has been cut-off, and the only light is cast by the flames rising from the cell windows. They are up there, in that state, because something in them had snapped. Deprived of water and food, brutalized day after day, these men had decided to take matters into their own hands, and take over part of the prison. She enters and walks into the darkness, stopping to pray with some of the men in the chapel, and then feels her way up to the third floor and to the heart of the riot. In a soft yet clear voice, she says to the leader, ‘you have to stop now. I know you have been suffering so much, but there is another way’. They throw their weapons out of the windows and go with Madre Antonia to sit with the warden and talk it all through; and so it was that night that an angel dressed in white spoke a word from God into the darkness of night: ‘do not be afraid’.

She enters and walks into the darkness, stopping to pray with some of the men in the chapel, and then feels her way up to the third floor and to the heart of the riot. In a soft yet clear voice, she says to the leader, ‘you have to stop now. I know you have been suffering so much, but there is another way’. They throw their weapons out of the windows and go with Madre Antonia to sit with the warden and talk it all through; and so it was that night that an angel dressed in white spoke a word from God into the darkness of night: ‘do not be afraid’. Many of our fears are visible and reasonable: like the fear of falling off tall buildings, or the fear of wild animals, or of large waves, or of the credit card bill after a particularly heavy month of shopping. Yet it is not the fear which is clear and obvious that we should be most concerned about, because much like my spider kept at more than arm’s length, if we can see it, we can avoid it. The fear we should be mindful of is the sort that does its work on us more quietly and unnoticed. It is such unseen fears that we have to be prepared to deal with.

Many of our fears are visible and reasonable: like the fear of falling off tall buildings, or the fear of wild animals, or of large waves, or of the credit card bill after a particularly heavy month of shopping. Yet it is not the fear which is clear and obvious that we should be most concerned about, because much like my spider kept at more than arm’s length, if we can see it, we can avoid it. The fear we should be mindful of is the sort that does its work on us more quietly and unnoticed. It is such unseen fears that we have to be prepared to deal with. I never heard Wayne’s confession; never knew why he was serving time. What I did learn from Wayne though, was how potent a force fear can be if you let it into your heart – not the fear of others, but the fear that tells you that this is all that your life will ever amount to. For Wayne, there were two freedoms he had chosen to walk toward. One was the freedom that lay at the end of his prison sentence. The other was to be set free on the inside, which for him arrived in the form of poetry. Wayne wrote poetry of a poignancy and potency I had never heard; words etched on a page written from a heart that knew that if it was ever to be free, it would have to dream that hope could be found beyond the horizon of his present fears and failings.

I never heard Wayne’s confession; never knew why he was serving time. What I did learn from Wayne though, was how potent a force fear can be if you let it into your heart – not the fear of others, but the fear that tells you that this is all that your life will ever amount to. For Wayne, there were two freedoms he had chosen to walk toward. One was the freedom that lay at the end of his prison sentence. The other was to be set free on the inside, which for him arrived in the form of poetry. Wayne wrote poetry of a poignancy and potency I had never heard; words etched on a page written from a heart that knew that if it was ever to be free, it would have to dream that hope could be found beyond the horizon of his present fears and failings.

I don’t know if Leonard Cohen ever made it to San Diego, but I wonder what he would have made of a scene I often like to cycle to on days-off. The particular spot is a bench on Mission Bay. From it it is possible to see in sharp relief two disparate worlds at once. To the Southwest is downtown San Diego, the heart of a city that so many people love to visit or to live in. It has a great climate, beautiful scenery, a laid back attitude to living, and if you have the means, a good life can be enjoyed here in the endless summer. Yet in the background of that American dream of a place, from my bench I can see another world, obscured by topography and showing little more than the hills in the distance, yet it is there, the city of Tijuana, Mexico, across the other side of the borderland we live in.

I don’t know if Leonard Cohen ever made it to San Diego, but I wonder what he would have made of a scene I often like to cycle to on days-off. The particular spot is a bench on Mission Bay. From it it is possible to see in sharp relief two disparate worlds at once. To the Southwest is downtown San Diego, the heart of a city that so many people love to visit or to live in. It has a great climate, beautiful scenery, a laid back attitude to living, and if you have the means, a good life can be enjoyed here in the endless summer. Yet in the background of that American dream of a place, from my bench I can see another world, obscured by topography and showing little more than the hills in the distance, yet it is there, the city of Tijuana, Mexico, across the other side of the borderland we live in. Some people would like to build a wall here. We already have a fence. You can see it at the retail outlets in Chula Vista. Between Banana Republic and Ralph Lauren the fence is close enough to make out the make of cars and the writing on billboards on the other side. Some exchanges are meant to keep us at a distance from one another, and others are intended for a closer encounter. This Saturday will see the latter as folks from my church – my church on both sides of the border in the dioceses of San Diego and Western Mexico – meet at the fence for a service of Holy Communion, passing sacred elements between the bars, like holy contraband at a prison visitation.

Some people would like to build a wall here. We already have a fence. You can see it at the retail outlets in Chula Vista. Between Banana Republic and Ralph Lauren the fence is close enough to make out the make of cars and the writing on billboards on the other side. Some exchanges are meant to keep us at a distance from one another, and others are intended for a closer encounter. This Saturday will see the latter as folks from my church – my church on both sides of the border in the dioceses of San Diego and Western Mexico – meet at the fence for a service of Holy Communion, passing sacred elements between the bars, like holy contraband at a prison visitation. We live in an open-sourced world yet in many ways also in profoundly closed-off societies. In Holland and France, Australia and Switzerland, Britain and the US, there is something of an opposite and equal reaction occurring to the seismic shifts of postmodernity. From a globalized market to the apparent end states of civic institutions, the digital age has thrown us into an intimacy not entirely of our own making and we are reacting like a patient weaned from their opioid too soon. Just a few years ago, we were celebrating the end of history and its triumph of liberal democratic values and multiculturalism. It is astounding to see how rapidly we have descended into a grim dystopian vision of nationalistic identity which leverages an economy of fear and misplaced anger. We hear that the reign of the ‘elites’ must come to an end, a blanket judgment cast upon intellectuals to politicians to anyone, frankly, who might claim any authorial voice other than the one purchased by wealth and outrage.

We live in an open-sourced world yet in many ways also in profoundly closed-off societies. In Holland and France, Australia and Switzerland, Britain and the US, there is something of an opposite and equal reaction occurring to the seismic shifts of postmodernity. From a globalized market to the apparent end states of civic institutions, the digital age has thrown us into an intimacy not entirely of our own making and we are reacting like a patient weaned from their opioid too soon. Just a few years ago, we were celebrating the end of history and its triumph of liberal democratic values and multiculturalism. It is astounding to see how rapidly we have descended into a grim dystopian vision of nationalistic identity which leverages an economy of fear and misplaced anger. We hear that the reign of the ‘elites’ must come to an end, a blanket judgment cast upon intellectuals to politicians to anyone, frankly, who might claim any authorial voice other than the one purchased by wealth and outrage. In such a torrid cultural landscape, it might be assumed that a borderland like San Diego-Tijuana would bear the marks of the apparent erosion of American values and the prospect of economic advancement for its citizens. Surely here the all-too porous lines of demarcation need shoring up. Get the bad ones out; keep the good ones in, is the mantra we hear. Yet as I sit on my bench and look out at the intersection of these two American worlds, what strikes me most is how little our life on this northern side of the line is influenced by the other world that lies to the south.

In such a torrid cultural landscape, it might be assumed that a borderland like San Diego-Tijuana would bear the marks of the apparent erosion of American values and the prospect of economic advancement for its citizens. Surely here the all-too porous lines of demarcation need shoring up. Get the bad ones out; keep the good ones in, is the mantra we hear. Yet as I sit on my bench and look out at the intersection of these two American worlds, what strikes me most is how little our life on this northern side of the line is influenced by the other world that lies to the south. Homi Bhabha, postcolonial theorist and all-round difficult read, says that the third space between the two sides of a cultural encounter is a space of difference, where the identity of each is split between its appearance and its repetition. Each one mimics the other, and each incrementally alters the other as the encounter leaves a resistant trace of hybridity, where nothing after is quite the same as it was before. True enough, there is a considerable flow of economic goods and services across the Mexican border in this part of the world, and the cultural mores and cuisines can be seen and ingested, yet we in this border town are hardly changed at all, even incrementally, by the profoundly other existence of our fellow human beings to the south. For the truth is that such change requires the bridging not the walling-off of cultures.

Homi Bhabha, postcolonial theorist and all-round difficult read, says that the third space between the two sides of a cultural encounter is a space of difference, where the identity of each is split between its appearance and its repetition. Each one mimics the other, and each incrementally alters the other as the encounter leaves a resistant trace of hybridity, where nothing after is quite the same as it was before. True enough, there is a considerable flow of economic goods and services across the Mexican border in this part of the world, and the cultural mores and cuisines can be seen and ingested, yet we in this border town are hardly changed at all, even incrementally, by the profoundly other existence of our fellow human beings to the south. For the truth is that such change requires the bridging not the walling-off of cultures. Bhabha argues that bridges are for gathering as much as they are for crossing. The sharing of the broken body and outpoured blood of Jesus through the cracks in the borderline offer a hint of such a beginning. For when flesh touches flesh, when eye meets eye, when sorrow and silence is shared, we have a chance at communion, a communion no wall can render asunder. The great challenge facing the will of those who wish to wall off this open wound of a border is that once communion has been felt and lived and loved, it is a belonging not easily forgotten. So, go to the fence, and to the walls, and to the places where the cracks in our misunderstanding start to show, and look for light. There is no perfect offering. Just us. Now. One body, in the Body who made us all.

Bhabha argues that bridges are for gathering as much as they are for crossing. The sharing of the broken body and outpoured blood of Jesus through the cracks in the borderline offer a hint of such a beginning. For when flesh touches flesh, when eye meets eye, when sorrow and silence is shared, we have a chance at communion, a communion no wall can render asunder. The great challenge facing the will of those who wish to wall off this open wound of a border is that once communion has been felt and lived and loved, it is a belonging not easily forgotten. So, go to the fence, and to the walls, and to the places where the cracks in our misunderstanding start to show, and look for light. There is no perfect offering. Just us. Now. One body, in the Body who made us all. I wonder if you might picture a scene. A priest and with him a lay minister of the church, some ashes in hand, and the world at our feet. Behind us is the blue expanse of the Pacific Ocean. Iridescent beauty as far as the eye can see, and not a bad backdrop for a piece of subversive theology. To our left is a man propped up against the concrete barrier that separates the boardwalk from the beach, with a sign that reads, ‘Homeless Vet: Any help, helps’. And to our right is the seemingly endless flow of traffic, of joggers and cyclists, men in business suits, and boys and girls dressed for a day at the beach. We are, unquestionably, out in the open, exposed, identifiably ecclesiastical in a decidedly post-religious corner of the world.

I wonder if you might picture a scene. A priest and with him a lay minister of the church, some ashes in hand, and the world at our feet. Behind us is the blue expanse of the Pacific Ocean. Iridescent beauty as far as the eye can see, and not a bad backdrop for a piece of subversive theology. To our left is a man propped up against the concrete barrier that separates the boardwalk from the beach, with a sign that reads, ‘Homeless Vet: Any help, helps’. And to our right is the seemingly endless flow of traffic, of joggers and cyclists, men in business suits, and boys and girls dressed for a day at the beach. We are, unquestionably, out in the open, exposed, identifiably ecclesiastical in a decidedly post-religious corner of the world. The truth about Christianity is that ours is a faith intended to be lived in the heart and out in the open, in the places and spaces where we will encounter others. Faith belongs, as does the Church, at the threshold of things, in the liminal borderlands of the world where people’s hurts and hopes will be met by those followers of Jesus who will encounter them where they are at, right where they need to be met. Yet for followers of Jesus, it is not merely for a day that one might brave the public life and take one’s faith out for a run. The Christian life is an ongoing vocation to see and be seen by others.

The truth about Christianity is that ours is a faith intended to be lived in the heart and out in the open, in the places and spaces where we will encounter others. Faith belongs, as does the Church, at the threshold of things, in the liminal borderlands of the world where people’s hurts and hopes will be met by those followers of Jesus who will encounter them where they are at, right where they need to be met. Yet for followers of Jesus, it is not merely for a day that one might brave the public life and take one’s faith out for a run. The Christian life is an ongoing vocation to see and be seen by others. In the end, grace always seeks to draw us out, and to cross the lines of demarcation that we draw between ourselves and others. May this be a season in the life we share as a nation that encourages fellow travelers to cross over such lines and meet one another just as they need to be met. In doing so, may they find that, as the needs of those around them are heard, and met, light arises in the darkness.

In the end, grace always seeks to draw us out, and to cross the lines of demarcation that we draw between ourselves and others. May this be a season in the life we share as a nation that encourages fellow travelers to cross over such lines and meet one another just as they need to be met. In doing so, may they find that, as the needs of those around them are heard, and met, light arises in the darkness.

I believe that the first time that I took my political ideas to the streets was about 20 years ago. I was in college, with, in truth, very little to complain about as far as my own life was going. I was a student at a university that was opening up my world. My school fees were paid by the government and each term I received a check from the Department of Education to help me with room and board. Aside from the weather, which I remember often as grey, life at university was pretty idyllic.

I believe that the first time that I took my political ideas to the streets was about 20 years ago. I was in college, with, in truth, very little to complain about as far as my own life was going. I was a student at a university that was opening up my world. My school fees were paid by the government and each term I received a check from the Department of Education to help me with room and board. Aside from the weather, which I remember often as grey, life at university was pretty idyllic. Some five years or so later in seminary, I had stepped from being a participant to becoming just a little bit more of an organizer, trying to stir the hearts of my fellow seminarians to join me at a peace rally, again organized in London. My theological studies were opening up new literary worlds and I can remember being particularly taken by the beautiful imagery of Amos, as he describes ‘justice rolling down like waters, and righteousness like an ever-flowing stream’. I wanted my practice to mesh with my theology.

Some five years or so later in seminary, I had stepped from being a participant to becoming just a little bit more of an organizer, trying to stir the hearts of my fellow seminarians to join me at a peace rally, again organized in London. My theological studies were opening up new literary worlds and I can remember being particularly taken by the beautiful imagery of Amos, as he describes ‘justice rolling down like waters, and righteousness like an ever-flowing stream’. I wanted my practice to mesh with my theology.

This long road brings me to the Women’s March on Washington, the standing in a bone-crunching crowded San Diego downtown street, unable to reach the rest of the contingent from our church, and doing all I could to keep my kids of getting knocked over through the hour and more speeches and rallying cries. Once more, after quite a hiatus, I was back on the streets on the march with others. I was there because while women are still underpaid and passed over more often for promotions at work than their male counterparts, while they still fall victim to more sexual assault and are objectified by billionaires and bigots alike, indeed while they are not yet treated with the full dignity that God bestows on all of us, man, woman and child, there is a compulsion to be there. Yet this time there was something more. As we stood there, literally rubbing shoulders with strangers, one of the women turned to me as said, “I want you to know why I am marching today.” She pointed at my daughter, “it’s for her. I’m marching for her”, and as she said it, I realized, so was I.

This long road brings me to the Women’s March on Washington, the standing in a bone-crunching crowded San Diego downtown street, unable to reach the rest of the contingent from our church, and doing all I could to keep my kids of getting knocked over through the hour and more speeches and rallying cries. Once more, after quite a hiatus, I was back on the streets on the march with others. I was there because while women are still underpaid and passed over more often for promotions at work than their male counterparts, while they still fall victim to more sexual assault and are objectified by billionaires and bigots alike, indeed while they are not yet treated with the full dignity that God bestows on all of us, man, woman and child, there is a compulsion to be there. Yet this time there was something more. As we stood there, literally rubbing shoulders with strangers, one of the women turned to me as said, “I want you to know why I am marching today.” She pointed at my daughter, “it’s for her. I’m marching for her”, and as she said it, I realized, so was I. At the same time, I was also there for something more than just her. Of course. We all were. And it was happening as we marched, an alternative picture of power replicated across cities in America and the world, from its epicenter in Washington to London to Paris to Sydney. Place by place, person by person, power was being renegotiated not in the corridors of power in Washington but on the streets of power’s lived articulation, where women and men and children make life together. Were there more people on those streets than had been there the day before at the President’s inauguration? Who can say? Those are alternative facts to the concerns of the people on those streets who brought their children to walk with them; alternative to the irrepressibility of the imagination wherein another power is birthing.

At the same time, I was also there for something more than just her. Of course. We all were. And it was happening as we marched, an alternative picture of power replicated across cities in America and the world, from its epicenter in Washington to London to Paris to Sydney. Place by place, person by person, power was being renegotiated not in the corridors of power in Washington but on the streets of power’s lived articulation, where women and men and children make life together. Were there more people on those streets than had been there the day before at the President’s inauguration? Who can say? Those are alternative facts to the concerns of the people on those streets who brought their children to walk with them; alternative to the irrepressibility of the imagination wherein another power is birthing.

In Dwight Zscheile’s edited collection, Cultivating Sent Communities: Missional Spiritual Formation, theologian Christian Scharen argues for the Church to adopt practices of ‘dispossession’ as it seeks to express its missional identity in contemporary society. Citing Donald MacKinnon who speaks of the need for Christians ‘to live an exposed life’ as integral to their ‘sent-ness’, dispossession implies a certain exposure to sight, a movement toward visibility for a church that for centuries has been accustomed to being seen on arrival as it were, as people crossed the threshold from street to sanctuary. Such a movement toward exposure, argues Scharen, is possible if grounded in the movement eternally present in the Trinity. Here he draws on Rowan Williams’ reflections on mission seen as ‘a matter of dispossession’ wherein the Church is sent, as the Son is sent of the Father, as life outpoured for the world, willingly dispossessed through the Spirit as God’s reconciliatory movement for the sake of the world. What Scharen invites us to imagine here is a kenotic, self-emptying common life wherein the identity of the Christian is not secured by our possession of the Church but in our receptivity to the other; in how much space we have made to receive the other through the outpouring of our selves. Such dispossession, thus enables the body of Christ to become a eucharistic people: taken, blessed, broken open, and given for the world.

In Dwight Zscheile’s edited collection, Cultivating Sent Communities: Missional Spiritual Formation, theologian Christian Scharen argues for the Church to adopt practices of ‘dispossession’ as it seeks to express its missional identity in contemporary society. Citing Donald MacKinnon who speaks of the need for Christians ‘to live an exposed life’ as integral to their ‘sent-ness’, dispossession implies a certain exposure to sight, a movement toward visibility for a church that for centuries has been accustomed to being seen on arrival as it were, as people crossed the threshold from street to sanctuary. Such a movement toward exposure, argues Scharen, is possible if grounded in the movement eternally present in the Trinity. Here he draws on Rowan Williams’ reflections on mission seen as ‘a matter of dispossession’ wherein the Church is sent, as the Son is sent of the Father, as life outpoured for the world, willingly dispossessed through the Spirit as God’s reconciliatory movement for the sake of the world. What Scharen invites us to imagine here is a kenotic, self-emptying common life wherein the identity of the Christian is not secured by our possession of the Church but in our receptivity to the other; in how much space we have made to receive the other through the outpouring of our selves. Such dispossession, thus enables the body of Christ to become a eucharistic people: taken, blessed, broken open, and given for the world. One of the images that Scharen uses to express what such a Church might look like is from Oslo, Norway, where one community, the Oslo Domkyrka, leaves its doors open not only through many of the weekday hours but through the night Friday to Saturday for what it calls Night Church. During these small hours of the night, the sanctuary becomes an open space where people can wander in and engage in various stations scattered around the building, lighting candles in a giant orb representing the world in one or folding prayers into Jesus’ sculpted open hands in another. The space is open like this from mid-afternoon on Friday until Saturday morning. A meditative prayer service is offered during the time and staff are available for conversation. In other parts of Scandinavia, night church happens several times a week, such as at the Church of Our Lady in Copenhagen, Denmark, open every Thursday, Friday and Sunday night.

One of the images that Scharen uses to express what such a Church might look like is from Oslo, Norway, where one community, the Oslo Domkyrka, leaves its doors open not only through many of the weekday hours but through the night Friday to Saturday for what it calls Night Church. During these small hours of the night, the sanctuary becomes an open space where people can wander in and engage in various stations scattered around the building, lighting candles in a giant orb representing the world in one or folding prayers into Jesus’ sculpted open hands in another. The space is open like this from mid-afternoon on Friday until Saturday morning. A meditative prayer service is offered during the time and staff are available for conversation. In other parts of Scandinavia, night church happens several times a week, such as at the Church of Our Lady in Copenhagen, Denmark, open every Thursday, Friday and Sunday night. So, can we be dispossessed? Can we learn to be learners of a Way that will beckon us to give ourselves away to God, shaped by the practices of a kenotic life shared with fellow travelers? Epiphany, the season of God’s manifestation, is a great time to ponder such things. ‘Sing a new church into being’, the hymn says. It goes on: ‘Dare to dream the vision promised, sprung from seed of what has been.’ New life is emerging, fruit born of the ancient seeds of our dispossession and of our hope.

So, can we be dispossessed? Can we learn to be learners of a Way that will beckon us to give ourselves away to God, shaped by the practices of a kenotic life shared with fellow travelers? Epiphany, the season of God’s manifestation, is a great time to ponder such things. ‘Sing a new church into being’, the hymn says. It goes on: ‘Dare to dream the vision promised, sprung from seed of what has been.’ New life is emerging, fruit born of the ancient seeds of our dispossession and of our hope.

This past week, our family headed out to an amusement park along with what felt like half the population of Orange County. We whizzed and whirled, span and splashed in hourly intervals as we otherwise whiled away our time in lines that snaked slowly around loudspeakers playing Frosty the Snowman on an unrelenting loop. And then came the question: who was going to go with the one daredevil child who wanted to be shot up into the air 250 feet and then dropped to the ground at 50 mph. The ride, if that is the word, is called ‘Supreme Scream’, which is actually a pretty accurate description of what happened in our case. “I’ll go with you”, I said, with unconscionable haste. And so they strapped us in, feet dangling, heart racing, face whitening. We waited, and waited, and shook more than a little. Then with a jolt, we began to rise.

This past week, our family headed out to an amusement park along with what felt like half the population of Orange County. We whizzed and whirled, span and splashed in hourly intervals as we otherwise whiled away our time in lines that snaked slowly around loudspeakers playing Frosty the Snowman on an unrelenting loop. And then came the question: who was going to go with the one daredevil child who wanted to be shot up into the air 250 feet and then dropped to the ground at 50 mph. The ride, if that is the word, is called ‘Supreme Scream’, which is actually a pretty accurate description of what happened in our case. “I’ll go with you”, I said, with unconscionable haste. And so they strapped us in, feet dangling, heart racing, face whitening. We waited, and waited, and shook more than a little. Then with a jolt, we began to rise. My reasoning, such as it is, for this new found commitment to being strapped in and scared out of my wits is simple. It is a brief yet essential new year’s resolution: draw closer to my children. Parenting to me is the most challenging and joyful and mystifying thing that I know. As I stumbled off rollercoaster after rollercoaster this week, I saw in the joy our children found in sharing that experience with us an affirmation that what any child wants perhaps more than anything from their parents is their solidarity, for them to be alongside them.

My reasoning, such as it is, for this new found commitment to being strapped in and scared out of my wits is simple. It is a brief yet essential new year’s resolution: draw closer to my children. Parenting to me is the most challenging and joyful and mystifying thing that I know. As I stumbled off rollercoaster after rollercoaster this week, I saw in the joy our children found in sharing that experience with us an affirmation that what any child wants perhaps more than anything from their parents is their solidarity, for them to be alongside them. This desire to be alongside others is a profound human need. Yet to draw near to others requires us to be willing to be seen as we really are. Solidarity does not spare us disappointment or pain as much as we might resolve to fill our lives with joy and fulfillment. And if we are to meet people as we are we have to be prepared to enter into a an authenticity most of us are not accustomed to. Yet in many ways, the vocation of the Christian life is one that calls us to live authentically. Rowan Williams speaks of Christian identity as that which we live into when all of our pretenses, the games we play with one another and with ourselves about who we are, are ended, and we accept the true name God alone calls us by.

This desire to be alongside others is a profound human need. Yet to draw near to others requires us to be willing to be seen as we really are. Solidarity does not spare us disappointment or pain as much as we might resolve to fill our lives with joy and fulfillment. And if we are to meet people as we are we have to be prepared to enter into a an authenticity most of us are not accustomed to. Yet in many ways, the vocation of the Christian life is one that calls us to live authentically. Rowan Williams speaks of Christian identity as that which we live into when all of our pretenses, the games we play with one another and with ourselves about who we are, are ended, and we accept the true name God alone calls us by.

This year, if you are truly struggling for something to buy for that relative back east whom you hope not to see more than a couple of times a decade, you could do worse than take a look at hallmark.com. For instance, there is the ‘Because Jesus’ mug. Indubitably, if you wish to confound Great Aunt Mabel, send her one of these and she will never speak to you again because all of her time will be occupied with trying to figure out ‘what’ because Jesus… Of course, that’s the trick, isn’t it. Jesus is best consumed, it would seem, when most open to modification. One could imagine an entire evangelism campaign centered on the ‘Because Jesus’ slogan. ‘Because Jesus’ is Jesus, I will stand on your street corner preaching loudly to the neighbors. ‘Because Jesus’ is happy to be Jesus, I will be happy to play Christian rock on my car stereo at high volume with the windows down at busy intersections. ‘Because Jesus’ is Jesus, we will invade your country until my Jesus is also your Jesus – although I suspect that last one might pre-date the mug by a year or two.

This year, if you are truly struggling for something to buy for that relative back east whom you hope not to see more than a couple of times a decade, you could do worse than take a look at hallmark.com. For instance, there is the ‘Because Jesus’ mug. Indubitably, if you wish to confound Great Aunt Mabel, send her one of these and she will never speak to you again because all of her time will be occupied with trying to figure out ‘what’ because Jesus… Of course, that’s the trick, isn’t it. Jesus is best consumed, it would seem, when most open to modification. One could imagine an entire evangelism campaign centered on the ‘Because Jesus’ slogan. ‘Because Jesus’ is Jesus, I will stand on your street corner preaching loudly to the neighbors. ‘Because Jesus’ is happy to be Jesus, I will be happy to play Christian rock on my car stereo at high volume with the windows down at busy intersections. ‘Because Jesus’ is Jesus, we will invade your country until my Jesus is also your Jesus – although I suspect that last one might pre-date the mug by a year or two.

I had gone shopping to look for a couple of Christmas cards. The first thing that struck me was how very difficult it was to find a card that was just about the birth of Christ and not also about something else. Card after card read something like this, ‘Joy to the World, the Lord is come…May Your Christmas be as Bright as Your Smile’. I couldn’t send that. I’m an Episcopalian, we’re not supposed to encourage smiling. I kept on looking, but in vain. I could feel the color drain out of my face as yet another promising piece of artwork was undermined by the reminder that the real reason for the season isn’t Jesus; it is me. I was everywhere, and there was little I could do to stop it. ‘Treat yourself to something special this Christmas’, it said as I tried to make my escape down the cosmetics aisle. Towering letters hung over me as I made a left down by the wine – ‘Have an extra merry Christmas on us’. It was all I could do to make it back to my office at church and put BBC‘s ‘Lessons and Carols from Kings’ on a repeated loop on YouTube.

I had gone shopping to look for a couple of Christmas cards. The first thing that struck me was how very difficult it was to find a card that was just about the birth of Christ and not also about something else. Card after card read something like this, ‘Joy to the World, the Lord is come…May Your Christmas be as Bright as Your Smile’. I couldn’t send that. I’m an Episcopalian, we’re not supposed to encourage smiling. I kept on looking, but in vain. I could feel the color drain out of my face as yet another promising piece of artwork was undermined by the reminder that the real reason for the season isn’t Jesus; it is me. I was everywhere, and there was little I could do to stop it. ‘Treat yourself to something special this Christmas’, it said as I tried to make my escape down the cosmetics aisle. Towering letters hung over me as I made a left down by the wine – ‘Have an extra merry Christmas on us’. It was all I could do to make it back to my office at church and put BBC‘s ‘Lessons and Carols from Kings’ on a repeated loop on YouTube. I lived a cocooned life, and I liked it, I guess. Yet, following a period of lying down in a dark room for a while, I realized something: Jesus was cocooned too. The Lord of all creation, lost somewhere between the super sale on candy canes and dashboard bobbing Santa heads. From this dark epiphany, the day only descended. That evening, my family and I went out to see a neighborhood nearby which at this time of year can be seen from space. We knew that we had arrived at the right place because the kids no longer needed to ask if we were there yet. In fact, they could no longer speak at all, such was the mesmerizing bedazzlement of the several million lights that twinkled in the night sky in San Diego suburbia. ‘Why are we here?’ I mumbled faintly to myself, but it was too late, I had been sucked into their sinister game. I too gawped and gaped and guffawed.

I lived a cocooned life, and I liked it, I guess. Yet, following a period of lying down in a dark room for a while, I realized something: Jesus was cocooned too. The Lord of all creation, lost somewhere between the super sale on candy canes and dashboard bobbing Santa heads. From this dark epiphany, the day only descended. That evening, my family and I went out to see a neighborhood nearby which at this time of year can be seen from space. We knew that we had arrived at the right place because the kids no longer needed to ask if we were there yet. In fact, they could no longer speak at all, such was the mesmerizing bedazzlement of the several million lights that twinkled in the night sky in San Diego suburbia. ‘Why are we here?’ I mumbled faintly to myself, but it was too late, I had been sucked into their sinister game. I too gawped and gaped and guffawed. If you have ever imagined a scene that you would construct outside of your house if neither money nor sanity were an object, then you would have imagined it too late – because it would have already happened here. My family and I had stumbled upon another reality altogether. Frosty was there, and the entire cast of Frozen, many times over, were with him. Santa was a staple, as were his reindeer. Yoda made a surprise appearance. One resident had even stuffed his car full of soft animals and pretended that this counted as a Christmas display by crudely placing a couple of fluorescent stars on his hood. I knew that should this man – for it had to be a man – ever came out of his house, eye contact would have to be avoided at all costs. It was at this moment, somewhere near to a giant Homer Simpson trapped in a giant Manhattan-themed snow globe that I decided that perhaps it wouldn’t be all that bad to give up the priest thing and move into illumination sales. This street alone could pay for my kids to go to college.

If you have ever imagined a scene that you would construct outside of your house if neither money nor sanity were an object, then you would have imagined it too late – because it would have already happened here. My family and I had stumbled upon another reality altogether. Frosty was there, and the entire cast of Frozen, many times over, were with him. Santa was a staple, as were his reindeer. Yoda made a surprise appearance. One resident had even stuffed his car full of soft animals and pretended that this counted as a Christmas display by crudely placing a couple of fluorescent stars on his hood. I knew that should this man – for it had to be a man – ever came out of his house, eye contact would have to be avoided at all costs. It was at this moment, somewhere near to a giant Homer Simpson trapped in a giant Manhattan-themed snow globe that I decided that perhaps it wouldn’t be all that bad to give up the priest thing and move into illumination sales. This street alone could pay for my kids to go to college. And then it happened. The renegade house. Simple. Understated. A crib. A message. A name surround by light. I was saved from what surely would have been a disastrous career as a salesman. Jesus was back; a holy insurgency amidst the festival of festivities. I stood there and admired it for a while. As I did, I imagined that in centuries gone by, perhaps it was so that the great, towering cathedrals of medieval Europe dominated the local landscape so much that it was the Church that made the locals’ heads swing as religion sought to dominate the cultural imagination. Perhaps, then, this is a fitting circle – that we have come back to the backwaters, to the one, anomalous house that had room for a family in flight and great need. The Light of the World born behind the main thoroughfare, in a place fit for animals and their muck. An insurgent God, whose love will not extinguish a dimly burning wick. There it was. Grace upon grace.

And then it happened. The renegade house. Simple. Understated. A crib. A message. A name surround by light. I was saved from what surely would have been a disastrous career as a salesman. Jesus was back; a holy insurgency amidst the festival of festivities. I stood there and admired it for a while. As I did, I imagined that in centuries gone by, perhaps it was so that the great, towering cathedrals of medieval Europe dominated the local landscape so much that it was the Church that made the locals’ heads swing as religion sought to dominate the cultural imagination. Perhaps, then, this is a fitting circle – that we have come back to the backwaters, to the one, anomalous house that had room for a family in flight and great need. The Light of the World born behind the main thoroughfare, in a place fit for animals and their muck. An insurgent God, whose love will not extinguish a dimly burning wick. There it was. Grace upon grace.

I was listening to a radio piece on NPR this week about the role of fake news in our country. A segment from the Diane Rehm Show was played wherein Scottie Nell Hughes, political editor of RightAlerts.com, claimed the following: “There’s no such thing, unfortunately, anymore of facts”. Syntax would also seem to be on the way out, but that is another issue. The first thing that struck me about this statement was that it was, rather ironically, not a fact. It was itself a piece of ‘fake news’. Facts, it turns out, are still with us. For instance, it is a fact, that now in my early 40’s, if I run around a soccer field for 90 minutes trying to keep up with players in their 20’s, I need to lie down in a dark room the following day while my body responds to the shock. No amount of fantasy will change that reality. I am no longer as spritely as I once was.

I was listening to a radio piece on NPR this week about the role of fake news in our country. A segment from the Diane Rehm Show was played wherein Scottie Nell Hughes, political editor of RightAlerts.com, claimed the following: “There’s no such thing, unfortunately, anymore of facts”. Syntax would also seem to be on the way out, but that is another issue. The first thing that struck me about this statement was that it was, rather ironically, not a fact. It was itself a piece of ‘fake news’. Facts, it turns out, are still with us. For instance, it is a fact, that now in my early 40’s, if I run around a soccer field for 90 minutes trying to keep up with players in their 20’s, I need to lie down in a dark room the following day while my body responds to the shock. No amount of fantasy will change that reality. I am no longer as spritely as I once was. This certainly seemed to be the train of thought that North Carolina resident Edgar Maddison Welch utilized when he fired his assault rifle in the Comet Ping Pong pizza restaurant in Washington last weekend because he believed it lay at the heart of a Democratic Party child sex-trafficking operation. Mr. Welch had apparently been motivated to carry out the attack by false allegations made on multiple social media sites. It is a living study in the power of persuasive falsehood. Mr. Welch seemingly believed that there were facts that supported the theory about the pizzeria being part of a sex-trafficking operation, even if those facts were not actually at his disposable the day he decided to carry out his own ‘investigation’.

This certainly seemed to be the train of thought that North Carolina resident Edgar Maddison Welch utilized when he fired his assault rifle in the Comet Ping Pong pizza restaurant in Washington last weekend because he believed it lay at the heart of a Democratic Party child sex-trafficking operation. Mr. Welch had apparently been motivated to carry out the attack by false allegations made on multiple social media sites. It is a living study in the power of persuasive falsehood. Mr. Welch seemingly believed that there were facts that supported the theory about the pizzeria being part of a sex-trafficking operation, even if those facts were not actually at his disposable the day he decided to carry out his own ‘investigation’. Of course, people have always been economical with the truth if it has suited them to do so. Adam and Eve didn’t get us off to a good start with that one. However, the current shift away from fidelity to the facts presents a certain crisis for society at large in an age when information is not only so readily available online, it is also disseminated across vast swaths of people via media that is able to influence individual and collective views and actions at a whim. The Roman Empire was good at propaganda. They emblazoned it amidst their civic spaces in the form of great archways and inscriptions making clear to the populations that they had subdued, that life in the Pax Romana was a life worth embracing. Resistance was not only futile, it was suicidal. What the Romans did not have was the ability to tweet or post or ping millions of people in a single communication. They did not operate on the principle of media saturation as a means to enter the minds of possibly otherwise reasonable people capable of discernment. Falsehood erodes our capacity for discerning truth. The more we are immersed in a universe of falsity, the harder it is to discern reality from the construction.

Of course, people have always been economical with the truth if it has suited them to do so. Adam and Eve didn’t get us off to a good start with that one. However, the current shift away from fidelity to the facts presents a certain crisis for society at large in an age when information is not only so readily available online, it is also disseminated across vast swaths of people via media that is able to influence individual and collective views and actions at a whim. The Roman Empire was good at propaganda. They emblazoned it amidst their civic spaces in the form of great archways and inscriptions making clear to the populations that they had subdued, that life in the Pax Romana was a life worth embracing. Resistance was not only futile, it was suicidal. What the Romans did not have was the ability to tweet or post or ping millions of people in a single communication. They did not operate on the principle of media saturation as a means to enter the minds of possibly otherwise reasonable people capable of discernment. Falsehood erodes our capacity for discerning truth. The more we are immersed in a universe of falsity, the harder it is to discern reality from the construction. Truth matters. Counter to Ms. Hughes’ assertion that we are in a post-factual age, the Church must take up a role that has always resided at the heart of its theological life: the practice of truth-telling. Liturgically, the act of truth-telling takes the form of confession. There can be no reconciliation, no real relationship, no opportunity for mercy to birth authentic forgiveness without that which we have done and that which we have failed to do being laid out in the open. Human beings need the light of truth-telling as fundamentally as they need air and water. Truth does indeed set us free because it provides us with the opportunity to start over again in our lives amidst the complexities of friendship and love, of common life and individual ambition. Truth enables grace to be felt in our lives as a living and transformational power. Without truth, grace remains only an abstract hope, not a present gift.

Truth matters. Counter to Ms. Hughes’ assertion that we are in a post-factual age, the Church must take up a role that has always resided at the heart of its theological life: the practice of truth-telling. Liturgically, the act of truth-telling takes the form of confession. There can be no reconciliation, no real relationship, no opportunity for mercy to birth authentic forgiveness without that which we have done and that which we have failed to do being laid out in the open. Human beings need the light of truth-telling as fundamentally as they need air and water. Truth does indeed set us free because it provides us with the opportunity to start over again in our lives amidst the complexities of friendship and love, of common life and individual ambition. Truth enables grace to be felt in our lives as a living and transformational power. Without truth, grace remains only an abstract hope, not a present gift. Dorothee Solle once remarked that the phrase, ‘The truth will make us free’, is an invocation to God so that the truth may not be forever buried in lies. We live in a time when the truth is indeed in danger of being buried. For every falsehood that is uttered about the ‘dangers’ of certain immigrant groups living in America, the promise of America as a nation of all-comers is diminished, until the values that we may have assumed were held in common are no longer visible in our life together; they are buried beneath a facade of fear and exclusion. Solle incites the Church to take up its vocation of truth-telling trusting in a God who does not stand in power over the world, but who is ‘grieved as we are’, ‘small like us’. It is in this ‘small God’ that we must place our hope, for the struggle to proclaim the truth about one another is a struggle that most often begins from the underside of history. The Church will need to sharpen its skills of attentive listening if it is to be a conduit for truth that has the capacity to set us all free. We will have to listen and we will have to speak, over and over, until our hearts beat with the longings of God himself. Truth upon truth, one life at a time.

Dorothee Solle once remarked that the phrase, ‘The truth will make us free’, is an invocation to God so that the truth may not be forever buried in lies. We live in a time when the truth is indeed in danger of being buried. For every falsehood that is uttered about the ‘dangers’ of certain immigrant groups living in America, the promise of America as a nation of all-comers is diminished, until the values that we may have assumed were held in common are no longer visible in our life together; they are buried beneath a facade of fear and exclusion. Solle incites the Church to take up its vocation of truth-telling trusting in a God who does not stand in power over the world, but who is ‘grieved as we are’, ‘small like us’. It is in this ‘small God’ that we must place our hope, for the struggle to proclaim the truth about one another is a struggle that most often begins from the underside of history. The Church will need to sharpen its skills of attentive listening if it is to be a conduit for truth that has the capacity to set us all free. We will have to listen and we will have to speak, over and over, until our hearts beat with the longings of God himself. Truth upon truth, one life at a time.

He is courageous and honest. He has stood up publicly to speak the truth about something to an entire nation that most of us can’t even tell our friends and family. He has been praised for how his bravery has opened up a country-wide conversation about something that really matters. And to boot, he is a politician. His name is Scott Ludlam, deputy leader of the Green Party and a Senator in the Australian Parliament. Last week he announced that he would be taking a leave of absence from the Senate in order to treat depression and anxiety. How many of us would have that fortitude?

He is courageous and honest. He has stood up publicly to speak the truth about something to an entire nation that most of us can’t even tell our friends and family. He has been praised for how his bravery has opened up a country-wide conversation about something that really matters. And to boot, he is a politician. His name is Scott Ludlam, deputy leader of the Green Party and a Senator in the Australian Parliament. Last week he announced that he would be taking a leave of absence from the Senate in order to treat depression and anxiety. How many of us would have that fortitude? Yet the prevalence of poor mental health, even among those demographics who suffer disproportionally in our country, needs to be considered alongside the relational impact that being designated as suffering from mental illness can have. In my own work on mental health and the Gospel of Mark (

Yet the prevalence of poor mental health, even among those demographics who suffer disproportionally in our country, needs to be considered alongside the relational impact that being designated as suffering from mental illness can have. In my own work on mental health and the Gospel of Mark ( The tragedy added to this is that a significant percentage of those who struggle with the psychological and social impact of mental illness face this cocktail of challenges alone, often untreated and kept hidden. Again, according to NAMI, only 41% of adults in the U.S. with a mental health condition received mental health services in the past year. Across ethnicities, the picture is worse: African Americans and Hispanic Americans used mental health services at about one-half the rate of Caucasian Americans in the past year and Asian Americans at about one-third the rate.

The tragedy added to this is that a significant percentage of those who struggle with the psychological and social impact of mental illness face this cocktail of challenges alone, often untreated and kept hidden. Again, according to NAMI, only 41% of adults in the U.S. with a mental health condition received mental health services in the past year. Across ethnicities, the picture is worse: African Americans and Hispanic Americans used mental health services at about one-half the rate of Caucasian Americans in the past year and Asian Americans at about one-third the rate. Perhaps the most generous thing that could be said of this election is that the best of us is yet to come. That is, after all, the great promise of democracy – we get to start over. We need to start again, profoundly so. People of faith, no matter how they vote today, can play a crucial part in that, for we are among those who trust in hope, not as an act of blind optimism but as the strength found in the God who makes all things new, even those parts of our lives that look well-past repair. Tomorrow we have a chance to start over. Let us each play our part and find our own voice of honesty and courage.

Perhaps the most generous thing that could be said of this election is that the best of us is yet to come. That is, after all, the great promise of democracy – we get to start over. We need to start again, profoundly so. People of faith, no matter how they vote today, can play a crucial part in that, for we are among those who trust in hope, not as an act of blind optimism but as the strength found in the God who makes all things new, even those parts of our lives that look well-past repair. Tomorrow we have a chance to start over. Let us each play our part and find our own voice of honesty and courage.